Chemical Formula/composition: CaCO3

and organic matter

Hardness: 3

Specific gravity: natural

2.71 and cultured ~2.75

Luster: pearly

and having the property known as orient

Toughness: poor,

tending to scratch, react with acids, and age by dehydration

Color: White,

yellow, black, pink, green; often enhanced by bleaching or dyes

Varieties: Several.

Pearls can be classified as fresh- or saltwater. Cultured pearls

can be named for their origins, for example Akoya, South Sea, Biwa

Localities: Worldwide.

Fine natural pearls are found in all oceans, in lakes, and rivers

Common simulants: Simulants

are not the same as cultured pearls. One important historical

simulant

is the Majorcan pearl, made from fish scales coating a glass

sphere.

Many other simulants occur.

Synthetics: Though

cultured pearls are analogous to synthetic gems, they are too important

in the world market to be treated as mere synthetics.

Pearls were probably among the first discovered gems, and because they need no cutting or treatment to enhance their beauty and are rare natural occurrences, they have most likely always been highly esteemed.

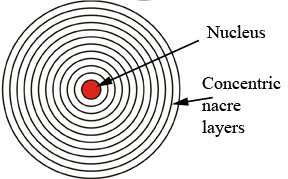

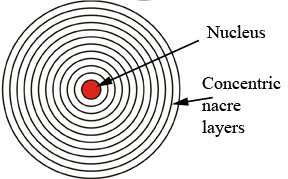

A pearl is grown by a bivalve (a mollusk such as a clam, oyster, or mussel) in response to an irritant. Bivalves that secrete pearls live in both fresh- and saltwater. The irritant in most cases is a parasite (not a grain of sand). The parasite, a worm or other creature, is walled off by a secretion of calcium carbonate and protein. The calcium carbonate is the same as the inorganic material that makes stalactites in caves, and the protein is called conchiolin. The combination of these two substances (calcium carbonate and protein) makes the pearl's nacre. The nacre is a lustrous deposit around the irritant and forms concentric layers.

Many concentric layers of nacre build up over a period of a few years creating a pearl. The internal pattern is much like that seen in a jawbreaker. The layers create a sheen or luster that has iridescence and is described as pearly luster or the pearl's orient.

A pearl is valued by its shape, size, luster, color, and surface perfection. Natural pearls are rarely spherical and this is the most desirable shape (for the obvious reason of its superior symmetry). The larger the better. The luster is a factor of how many layers of nacre are present and the surface perfection. The color may be related to the species of bivalve, the environment in which the bivalve grew, or how the pearl was treated after harvesting.

Cultured Pearls

Nucleated pearls

Most pearls sold today, perhaps greater than 90%, are not natural, but are artificially induced in a bivalve by surgically implanting an irritant. These induced pearls grown in cultivated bivalves are called cultured pearls. Several countries and notable figures have contributed to pearl cultivation. Carolus Linnaeus (1707-1784), a famous botanist who invented the binomial classification of species, invented a way to culture round freshwater pearls in mussels. As well, induced pearls or nacre-covered objects date back to the 1300s in ancient China.

However, pearl culturing as we know it today, to create round perfect specimens, was perfected in Japan in the early 1900s . The method uses a bead of calcium carbonate that replaces the irritating parasite and acts as a nucleus for nacre secretion that ensures a spherical pearl. The name Kokichi Mikimoto is synonymous with fine cultured pearls, but Mikimoto's method of culturing called the whole wrap is not used today. The method used was invented by Tokichi Nishikawa and is called the piece method.

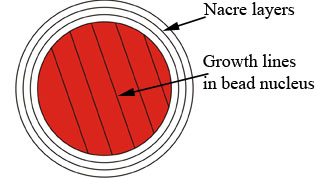

The piece method involves a surgical operation on the bivalve that implants a spherical nucleus or bead of calcium carbonate and a piece of tissue cut from the mantle of another oyster. The mantle is the tissue that secretes (makes) the bivalve's shell (which is calcium carbonate) and the pearl. After the operation, the oyster is returned to the water, hung from a special raft, cared for, and grown for a period of time. Harvesting releases the pearl but kills the oyster. The oyster of choice for pearl growth used by the Japanese industry is the Akoya oyster and the pearls from these saltwater oysters are called Akoya pearls. These pearls have only a relatively thin coating of nacre around the bead nucleus and yet look as good as natural pearls. The thickness of the nacre layer may vary from 0.1 mm to 1 mm (see illustration below). Clearly a thicker coat of nacre will ensure a longer lasting pearl. Thin layers may be worn away within only a few years of use.

Nucleated pearls on display on 5th Avenue,

Manhattan.

A 40+ year old Akoya oyster with a mabe pearl. Brittle and dried

with age.

Mabe pearls

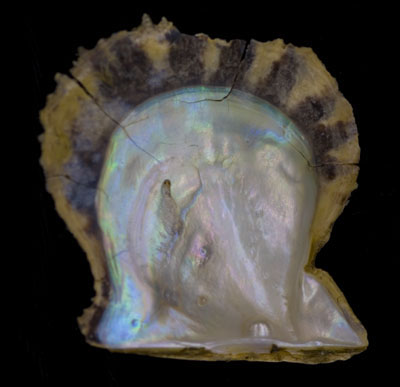

These are not true pearls but are grown by pasting a half-sphere of plastic or mineral matter to the shell of an oyster. They are essentially artificially induced blister pearls. Blister pearls are natural growths from the shell of a mollusk typically induced by a parasite. The Mabe pearl is removed from the oyster shell by cutting and then the hollow portion is filled in and a piece of mother of pearl can be used to cap the pearl, making it semispherical.

Non-nucleated Pearls

A separate method implants only a piece of tissue with no nucleus

into a freshwater clam or mussel. A second batch of pearls may

form

in these mussels spontaneously. (Spontaneous pearls also form in some

previously

nucleated oysters; these are called Keshi Pearls, non-nucleated pearls

from the Pacific.) This method creates a pearl without a bead

nucleus.

The freshwater pearls of this type are pure nacre and can be very

lustrous

and attractive. Freshwater pearls of this type, however, will not

be round. They tend to be oval and irregularly shaped.

Other Uses of Pearls

Pearls have been used in funerary rituals by both the people of India and Native Americans. Hindu funerals may use pearls as a symbol. The pearls are placed in the mouth of the deceased. Typically these would have been very small pearls (seed pearls) of not too great a value (Kunz and Stevenson, 1908). In the USA pearls have been reported in burial mounds in both Georgia and the Ohio Valley. The mound-building culture in the Midwest used pearls, sometimes in great quantities for burial rituals. Pearls were usually pierced but have also been found inlaid into bears' canine teeth. These freshwater pearls were found in streams and lakes of the region, but there does not seem to have been a great trading of them. Sometimes great quantities of pearls have been found, but sadly they are greatly deteriorated from the long period of burial in the mounds.

Pearls of low quality have been used as a powder in a preparation referred to as paan that contains betel nuts and other substances placed in betel nut leaf and chewed. More recently, a preparation of powdered pearls, or pearl dust, has been sold with marketing purporting that pearls have unsubstantiated effects on the libido!

Fake pearls

Even though cultured pearls are relatively inexpensive, imitation

pearls

are still quite common. They can be made of plastic, glass, or

may

be composite. One of the better types of imitation pearl is the

Majorca

Pearl. These are glass beads that are painted or coated on the

inside

of a hollow glass bead with a substance called "essence

d'orient."

The essence d'orient is created from the scales of fish. The

glass

bead is then filled with wax. Other fake pearls are made from

pieces

of mother-of-pearl that are cut to a sphere.

Links

American

Museum of Natural History Pearls Exhibit Website (no longer on display at

museum)

Wikipedia article on nacre (the scientific term for mother-of-pearl)

US Geological Survey article on Pearls